We’ve walked a lot of people through Hohenadel House, and one of the first questions out of everyone’s mouth is always: How old is this place?!

A simple question, but a frustrating one. The land has been settled since colonial times so historical associations are tantalizing and plentiful. Unfortunately, Philadelphia’s record-keeping has been maddeningly shoddy from the get-go.

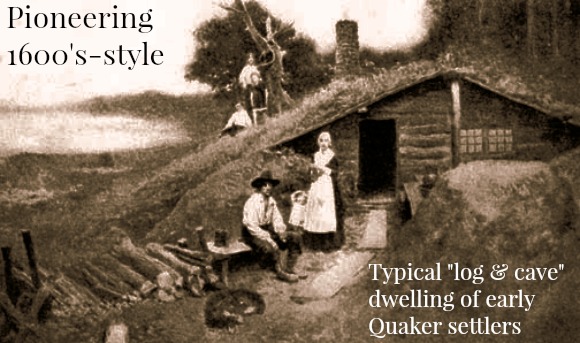

But then, it’s not like the the area’s first settlers arrived with blueprints and permit applications. For the first 200 hundred years — easy! — the inhabitants of the Philadelphia area were in survival mode. Not a whole lot of paperwork is completed in survival mode.

No doubt many houses back then started out as emergency shelters for bewildered colonists landing in the New World for the first time.

Pioneering Quakers in the mid-1600’s lived in riverbank “caves” (originally muskrat holes) until Penn showed up in 1682 — and even then, folks generally built houses near their caves, which were still used for storage and protection in inclement weather. In many cases, they were even fit with chimneys & thatched roofs. The line between “cave” and “house” was kinda blurry for awhile.

Streets? In those early days, people got around by way of Native American footpaths, so even if you managed to catch the name, good luck getting the spelling right. Of course, original settlers forged their own paths, too, but with necessity in mind, not so much public planning.

To top it off, our earliest maps tend to be wildly incomplete and out of scale. They’re often remiss of existing structures and geographical features — and some will even show roads/structures intended to be built, but never finished. No wonder that before Consolidation with Philadelphia in 1854, land and housing records tend to disagree on what was where.

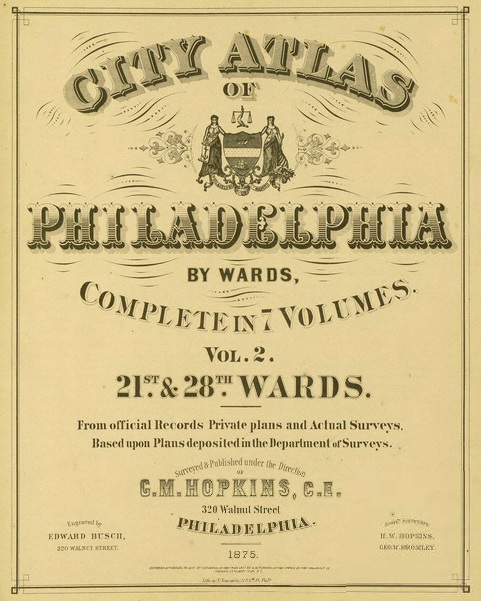

Our particular area’s administrative “Dark Ages” in fact stretch to the 1870’s, when this district finally was accurately mapped by the G. M. Hopkins Company, a Philadelphia enterprise whose maps set the bar for cartography on the Eastern Seaboard.

“Hopkins maps” combined fire insurance plats and county atlases to create real estate maps that clearly delineated properties, showing owner names, lot & block numbers, dimensions, street widths and other landmarks including churches, cemeteries, mills, schools, roads, railroads, lakes, ponds, rivers and creeks.

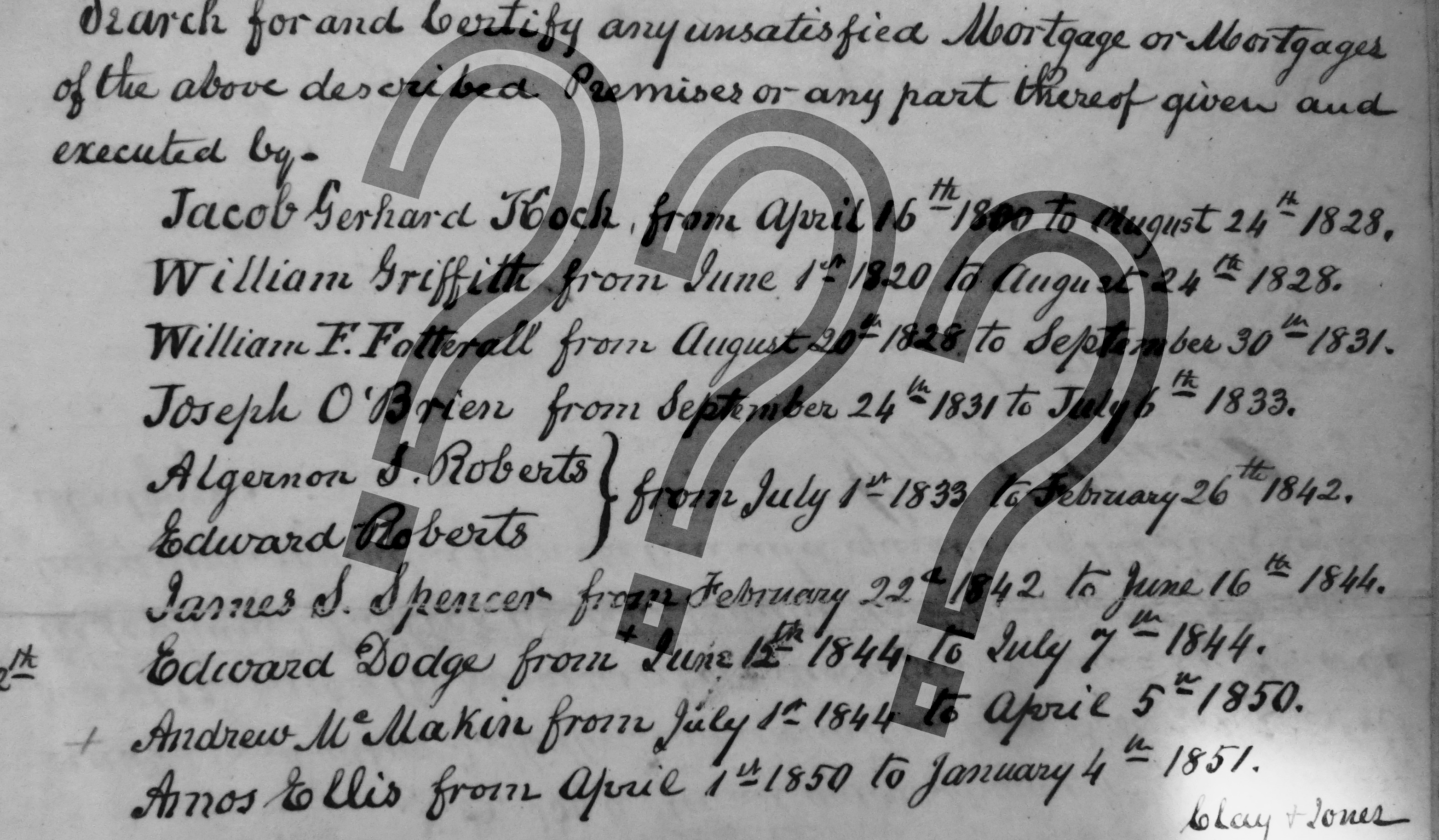

Hohenadel House is on our area’s 1875 Hopkins map, so we know it’s at the very least 139 years old. But wait! An 1870 photo of Falls of Schuylkill Baptist Church next door clearly shows Hohenadel House so now we’re at 144 years old. But wait! The church’s archives produced an 1852 deed for the construction of a house for/by Amos Ellis — if the house was built then, that’d take us to 162 years. And there’s no way of knowing if Amos Ellis was building new or adding to an existing structure, so we could theoretically go back even further…

We’d love to! But what to do, without reliable documentation?

Aaron Bechtel‘s got a few ideas. A friend of EastFallsHouse, he’s an antique bottle expert and local brewery historian who also happens to know a lot about privy digging. And topography. And, by trade, construction & woodworking. He was the obvious choice to help investigate Hohenadel House’s “secret passage” described by Lawrence Ponzek, who grew up here in the 70’s and told us his brothers & friends used to follow it to a side street below.

When we checked the space out later, there was no entrance to any passage we could find, but the area seemed to be loosely packed with earth, perhaps recently filled? Aaron came out with his metal “privy probe” and poked around under Hohenadel House’s back stairs. Solid wall, at every angle.

Aaron scouted the terrain and then tracked back to another, smaller stairway that seemed to be more in line with the slope any such passage would appear to need to follow to Dutch Hollow:

Nothing there, either. Hopefully, Lawrence will be visiting soon, and able to point us in the right direction.

Aaron also took a look at the house’s newly-discovered antique window shutters and sized them up based on his knowledge of period carpentry. Let’s get the bummer outta the way: these are most likely not original to the house. Boo.

Three things tipped Aaron off:

First (and this is all just speculation), he feels the round-headed screws are probably early 20th century — older shutters would have square headed nails, most likely. Second, the shutters appear to be a part of the windows, which have Deco-type embellishments. And finally, the galvanized chain window drives place these windows/shutters probably around 1910 – 1920’s.

Aaron also noted different layers of lead primer, oil paint and acrylic paint — the bright white wasn’t available until after WWII but the cream colors would certainly be consistent with Victorian revival interior paint accents (what a coincidence, Felicite chose a similar cream color for the downstairs living space).

And check it out — pocket shutters! Also called “privacy shutters,” they were designed to slide into cavities built into plaster walls of early homes. New Englanders knew them as “Indian shutters” due to the colorful myth that they were somehow raid-proof.

In this house’s heyday during the early part of the 20th century, this style of window dressing was a popular way to showcase decorative woodworking. Though the years, the stately window trim has been painted and painted over, again and again. Thick layers, just dying to be peeled.

Definitely some antique pigments in this house — not just in the windows, but there are so many old nooks left to explore. While the romance of uncovering secret passages & 200-year-old design features was pretty thrilling, so is watching the pieces of Hohenadel House’s real history come together after all this time.

We’ll get Aaron out for another look at the house when he has more time to employ his historical sleuthing skills on the rest of the house, most likely after we meet with Lawrence Ponzek (or someone who can show us where the passage was).

Meanwhile, it’s actually kinda good that the shutters Felicite and Sean impulsively scraped out of obscurity weren’t two centuries old — 19th century paint can kill you!

In the early 1800’s, a brilliant shade of emerald green paint was created by using copper arsenite — aka arsenic, aka rat poison. Often called “Paris Green,” it was also added it to wallpaper, furnishings, clothing and even used on children’s toys, causing rampant chronic arsenic poisoning as well as the occasional sudden reaction or even early death for sensitive sorts.

Well that coulda been ugly.

And now the next logical question, forgive us but we’re wondering: when’s Sherwin Williams gonna add an arsenic-less “Paris Green” to their Historic Collection?

(for guest rooms and Mother-in-Law suites — a subtle way to suggest lengthy stays could be hazardous to your health, ha)

Final Fun Fact: Napoleon Bonaparte decorated many of his houses with this vibrant green pigment, and regularly enjoyed long, hot, steamy baths where he no doubt inhaled enough arsenic fumes to explain the amount found in his hair at the time of his death (so much for rumors that he was poisoned by the husband of his married lover).

One thought on “How Old is this House? Hunting for Clues in Nails, Paint and Window Sashes”