It’s amazing what kind of history you can find under your feet. Aaron Bechtel, bottle collector and local historian, made his first find by accident in 2006 on a hike in the Wissahickon.

He happened to look below him while crossing a bridge, and noticed a vast old dump of glass demijohns (3 – 5 gallon bottles) sticking out of the ground. Though most were smashed, five were intact. He studied the bottles for clues online, and discovered they were quite antique — probably from around the turn of the 20th Century.

Their number and location provided even more clues:

“They couldn’t be from a private resident. There were too many of them. That, and their location, convinced me that they were from one of the old roadhouses along Lincoln Drive. The Maple Springs Hotel (founded 1794), maybe, or Tommy Llwellyn’s Old Log Cabin (1840).”

(Maybe they were the ones used by trained bears?)

The find was the beginning of a passion for bottle collecting that’s given Aaron an unusual perspective into the history of East Falls. Some historians rely on ancient texts or uncovered skeletons. Aaron sees history in East Falls through the wide variety of antique bottles he uncovers.

The bottles he’s unearthed reveal the evolution of bottle making in our area. Although many characteristics are required to properly date a bottle, color and shape are often the first steps in the process.

“You can tell a lot about a bottle by its color. Not only the general time period it came from but also what type of product was in it.”

On eBay and auction blocks everywhere, the most colorful antique glass brings the highest bidders. Of the many colors of glass bottles, only three are “natural”: Green, Amber and Aqua. These shades are caused by the composition of the sand reacting to the temperatures of the firing process. (Fun Fact: clear glass is not a natural color, but requires a clarifying agent).

1. Green

Green colors, circ: 1750-1920

Green bottles represent perhaps the greatest range of colors, running the gamut from very light (yellowish green) to extremely dark (emerald). After 1875, green was rarely used for beer bottles, with bottlers opting for brown glass instead.

2. Amber (or brown)

Circa: 1844-Present

Brown is often called amber by collectors and hues range from yellow to almost black. The brown color became popular after 1880 when it was used extensively in the bottling of beer. The dark color was used because it provides the best protection from ultraviolet light, which causes oxidation and other photochemical reactions in beer. Brown is still the primary color of today’s beer bottles.

Like the greens, amber colors were produced from the natural impurities in glass (i.e., iron & manganese) as well as from color additives such as nickel, sulfur, and in particular carbon, which was added to the glass batch in the form of coal, charcoal, or even wood chips.

3. Aqua

Circa: 1848-1920

Short for aquamarine, this is the most common color of antique bottle. This color was rarely used for beer bottles before 1850 but some examples exist.

Aqua bottles became rare after the 1920s, when clear glass became popular among producers (such as in the food industry) who wanted their product to be visible to the buyer.

Shapes of the past

Like color variations, there are numerous types of bottle styles, several of which appear in the Falls, including porters, malt extract, champagne, and ponies. Unlike today’s machined bottles, bottle shapes could vary widely from one town to another and were dependent on the skills of glassblowers using pontil rods and rolling the molten glass on wooden boards (or later, a mold).

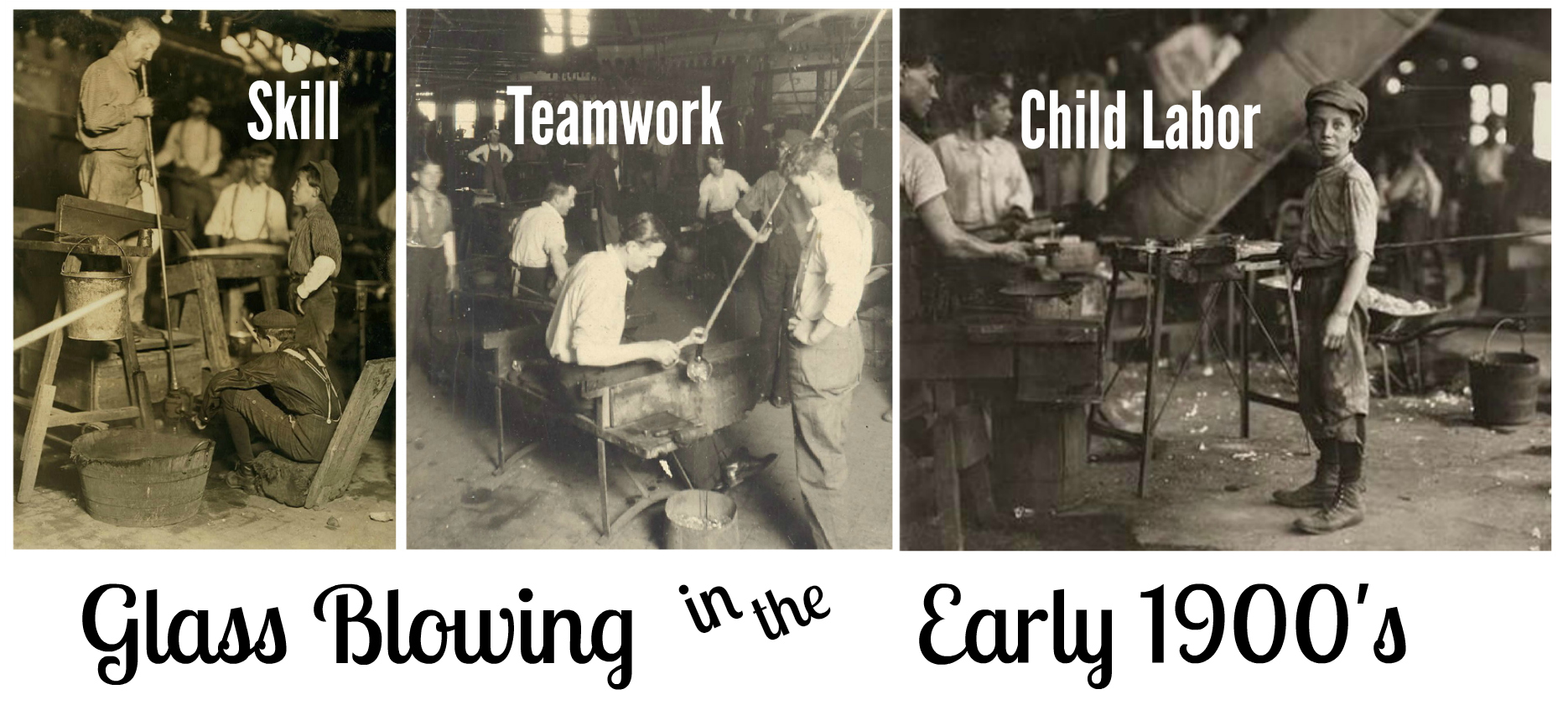

Glass blowing was an art as well as an industry. A blower stood above his assistant who closed the mold around the “parison” (rounded mass of molten glass) and then snipped it off once the bottle fully expanded, forming the opening. For Aaron, the resulting imperfections are what make the bottles so interesting and collectible.

“They are incredibly unique. Unlike machines, you get something that has character. It’s a reflection of the person and the process making that particular bottle.”

Even the evolution of bottle shapes was not uniform. Porters, for instance, endured for two centuries, even after the Export style (still used today) became popular in the 1870s.

What drove the changes? According to Aaron, bottle shapes were often dictated by regional preferences or were driven simply by marketing efforts — that is, the brewer wanted to stand out from the crowd.

Bottles from the Falls

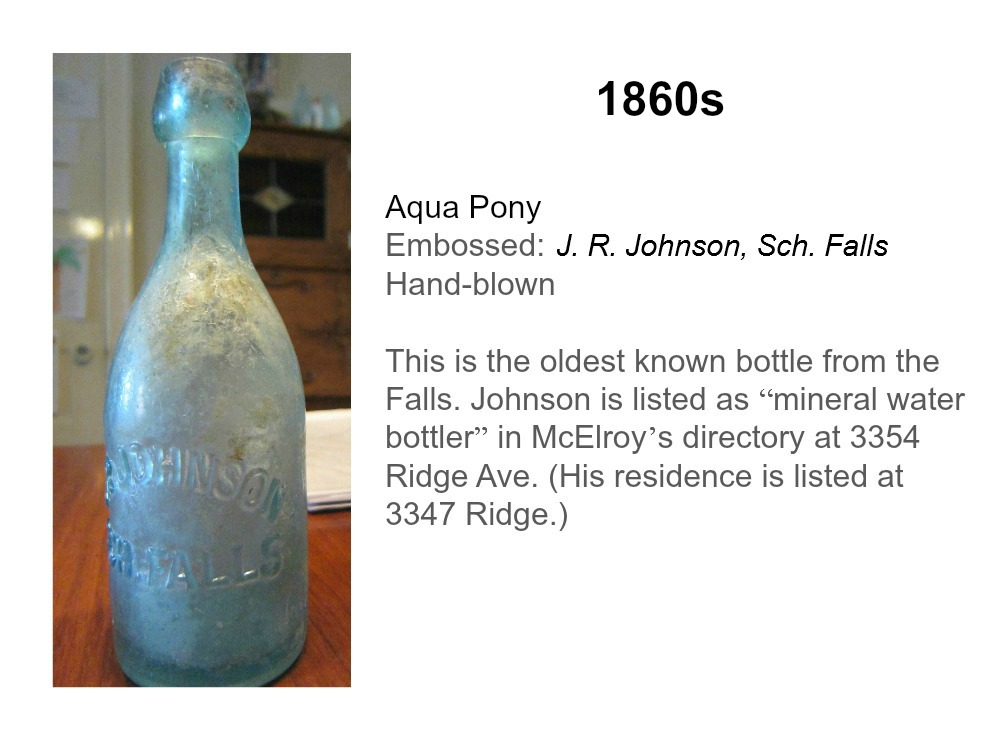

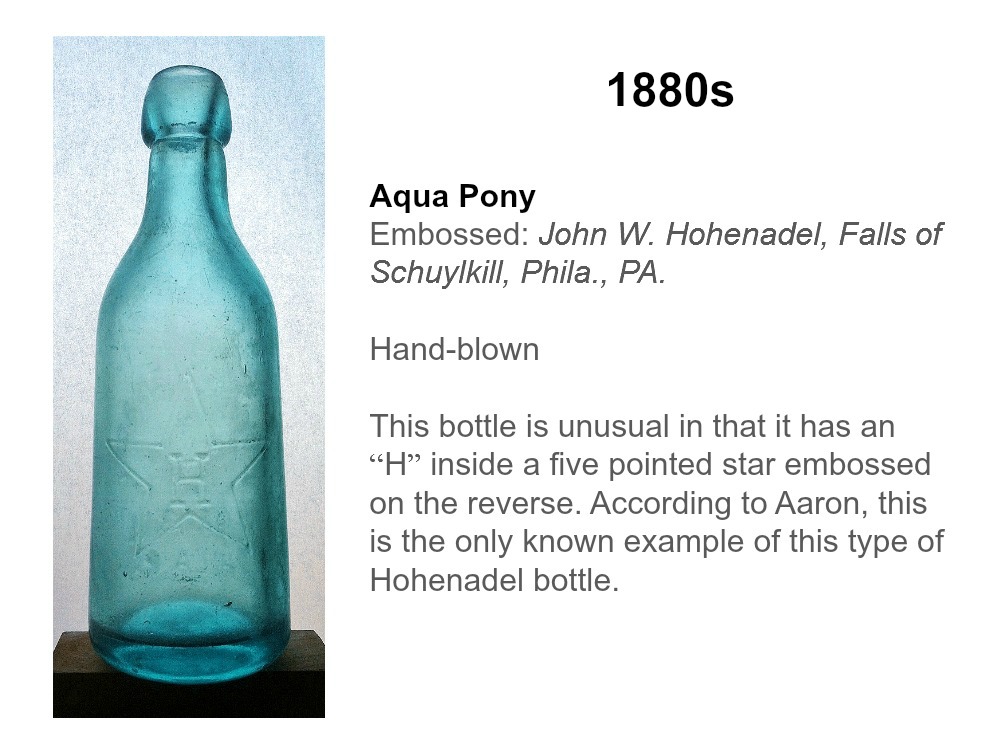

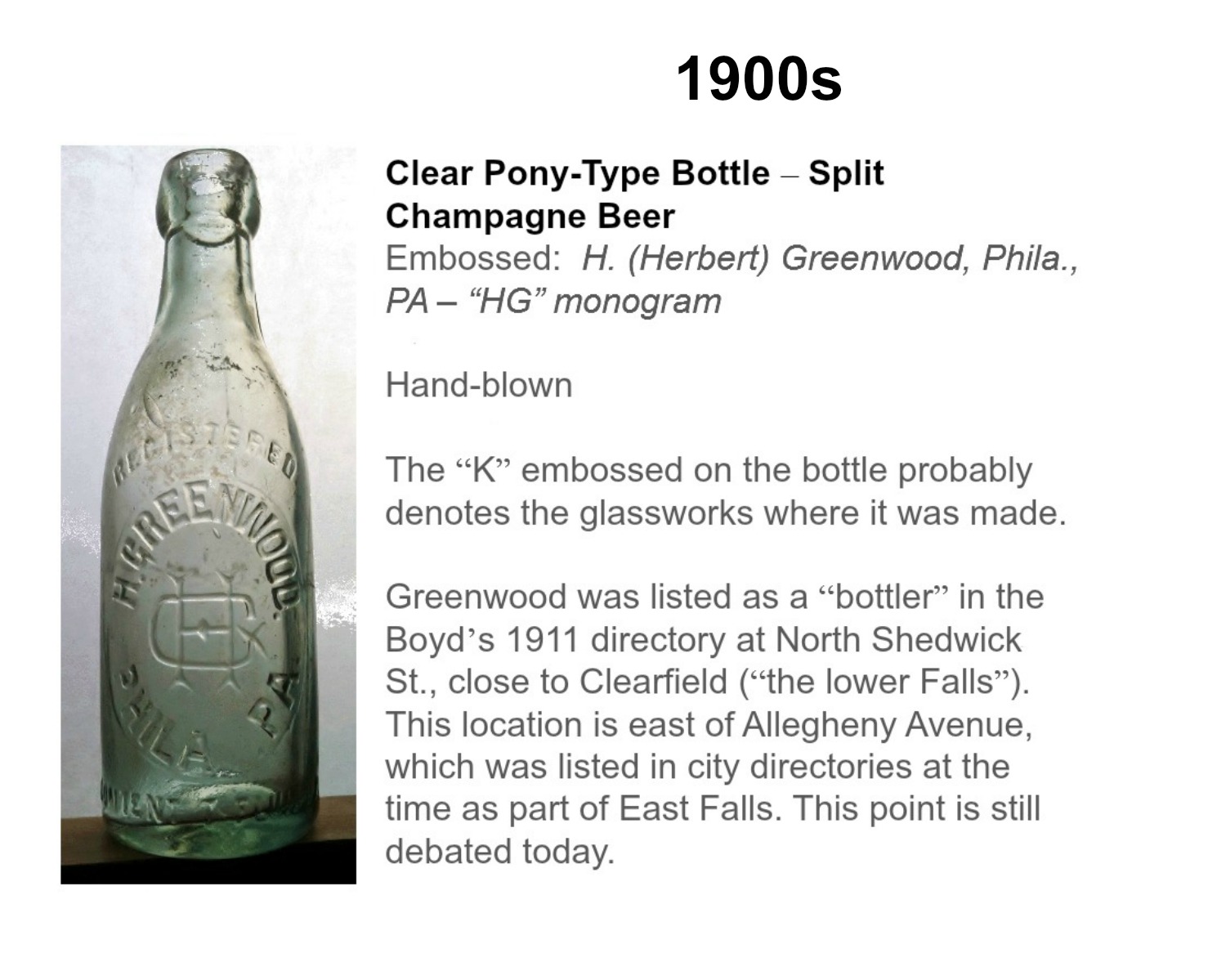

A few samples (by decade) from Aaron’s collection:

An Amateur Historic Excavator

Digging up a bottle is often the easiest part of Aaron’s job. His research in identifying likely excavation sites is exhaustive. He relies on maps, geography, city directories and historical records to develop an understanding of a site’s history and a context for the articles he uncovers.

For all his efforts, he often has to work equally hard against a common stereotype about bottle diggers.

We’re often seen as pirates or looters or some other derogatory term that is just loaded language. It’s a very common refrain in the archeological community.

This fails to describe what most bottle diggers-slash-amateur historic excavators do: contribute extensively to regional databases and perform ongoing research on bottlers, glasshouses, bottling works, breweries, apothecaries and pharmacies, dairies, etc. as well as excavated sites. This information preserves a “physical heritage” that might otherwise be lost.

There isn’t enough money (or archaeologists) to undertake excavations of “less important sites” like neighborhood privies or abandoned lots or old landfills. Every day, the bulldozers level more and more sites, disconnecting us from the treasures of our past — not just glass and pottery worth money today, but information that gives us all greater understanding of our history and local culture.

Sure, Aaron sells some of the bottles he finds — duplicates, mostly — and like other collectors he keeps an eye out for ones with market value, like old mason jars from the 30’s that make popular wedding centerpieces. His heart, however, is in the old hand-blown stuff. Pick one of those, and he can tell you where he dug it, who made it, what it might have been used for, and he probably’ll show you a map of the area and time it came from — sometimes the time of day.

Amazing what tales an old piece of glass can tell. Stay tuned for more information on privy digging and urban artifact-hunting from Aaron and EFHS!